This is an excerpt from a chapel talk I gave a couple years ago on the spiritual discipline of fasting.

The Fallen Feasting of the First Adam

God’s first specific command is a command to fast and feast in a proper way. You can feast from all of this goodness, but not of one particular tree. Even in God’s good creation, a certain kind of fasting was called for, a fasting that recognized that God is God and we are not. Fasting helps us to understand our limits and God’s sovereignty. Fasting helps to properly “place” us within God’s world. But God’s good creation also had plenty of room for feasting. God tells Adam and Eve to enjoy the abundant goodness of all other trees in the garden. He had made these trees in part to provide the sustenance humans need to live and flourish in his world.

The intertwinement of fasting and feasting is important. If all they did was feast, there would be a strong likelihood that they would forget that the source of all this goodness is not the fruitful trees but God. So when God sets apart a tree that they may not eat from, it is a sign to them of their limits—they are the image of God, not God—and it is also a remembrance that the source of all good things is not something within creation but the Creator. So fasting from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil is not simply “fasting.” It is a recognition that we depend upon God, not food or anything else, for our life and abundance. This fasting inscribes them within an entire worldview and narrative. It is a fast that proclaims a vision of the entire world in which the man and woman find themselves, with God as good and gracious provider and humans as his dependent representatives in the world he has created.

But the man and the woman choose to feast. And just as fasting is never just fasting, so feasting is never just feasting. This feast was a declaration of independence and rejection. In this feast, the man and woman rejected the world as a gift of the good Creator and instead proclaimed that they would harvest the goods of the world and recognize no bounds on their consumption. This is a consuming feast, a feast that knows no boundaries and no limits. A consuming feast that will promote a vision of the world as a world existing to serve only my needs, my sinful wants, my sinful desires. Not only trees and fruits, but all good things given by the Creator will now be seen not as gifts, but as simply givens, there for my taking to do with what I will. This is a consuming feast that will, in the end, cave in on itself like a black hole, consuming the consumer and all else that comes within its orbit. Indeed, within a few short chapters of Genesis, we see that sin entails a de-creation, as God’s good world succumbs to the formlessness and void of the flood, with only Noah and his family escaping. Fallen feasting seems good at the time, but its end is death.

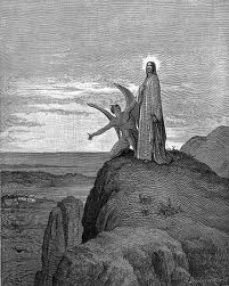

The Redemptive Fasting of the Second Adam (Matthew 4:1-4; Matthew 6:16-34)

The Second Adam is not feasting in a lush garden, but fasting in the desert of the real, the fallen world. When Jesus responds to the tempter, he is clear that it is not food but God who ultimately sustains us. Our practice of fasting helps us to remember that we depend for our existence and well-being ultimately on the Creator, not anything in creation, including food.

Jesus assumes that his disciples are going to fast. In Luke 5:35, Jesus says his followers will fast in the future, when he has ascended. But fasting is not done to impress others with how spiritual we are. In fact, Jesus says don’t let others know that you are doing this.

We should recognize that nothing shows a lack of dependence on God like the willingness to store up the world’s treasures for ourselves. Jesus says do not worry about your food or clothes; don’t worry about tomorrow. Now, this seems really hard. The problem is, we read these as Jesus telling us something impossible. He’s describing a radical kind of life that we can’t really do anyway. Maybe crazy monks or Shane Claiborne can just leave it all behind, but we can’t. If you’re going to be a pastor, youth minister, social worker, worship leader, educator, business person, or whatever, we have to plan for the future. But the rhetorical question Jesus poses, “what shall we eat?” comes from an Old Testament text about the Sabbath year: Leviticus 25.

In Leviticus 25, God commands Israel regarding the Sabbath year and year of Jubilee. For six years, the people were to harvest their fields and prune their vines. Every seven years, the land was to have a Sabbath rest. No harvesting, no pruning. On the one hand, this is a fast, a fast from working. Like Adam and Eve in the Garden, the people of Israel were called to recognize that what sustains them is not the fruit of the land, but God. This work stoppage, this fast from working, was a declaration of dependence on God.

But this was also a feast. God said that every sixth year he would provide more than enough to sustain the people through the Sabbath year and beyond. Deuteronomy 15 clarifies that this year also brings with it a proclamation of debt forgiveness. (All student loans will be forgiven!) Why? Deutueronomy 15:4 tells us so that “there will be no poor among you.” This was a year of feasting and partying. In that seventh year, there was food. Food was there, and the food of the land was for everyone: male and female, Jew and Gentile, slave and free. The Sabbath year is a year of leveling, a year in which all partake of God’s abundant provision, rejoice in the forgiveness of debts, and gather around the Lord’s table that he sets before his children.

So when Jesus echoes the question “What shall we eat?” and talks about pursuing the kingdom first, he is calling us to embrace the fasting and feasting of the Sabbath year. Jesus’ followers fast to inscribe into our very bodies the reality that we do not serve the god Mammon. Fasting gives us a new vision of the universe and all the good things the Father provides. We are called to write love not on our arms, but in our bellies. We therefore plow and harvest responsibly, but we do so not to hoard but so that there will be no needy among us, as Deut. 15:4 promises and Acts 4:34 fulfills. For the early church, the Sabbath year was not a once-every-seven-years proclamation, but a way of life. Indeed, we pray “give us this day our daily bread,” and “forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors.”

Jesus calls to renounce the consuming feast of the first Adam in order to embrace the self-giving fast of the Second Adam. In fasting, we are able to see the world as God sees it; we are able to pursue the kingdom first and trust that everything else will follow. Like the boy with five loaves and two fishes, we can let go of what we have and, when we do, we will miraculously find that the Lord of the feast provides all that we need and more. The Church, then, as the New Eve, ought to follow the lead of Christ her husband, resist temptation and remember that we do not live by bread alone but by God’s Word. The question is, in a world shaped by gluttony and greed, whether we have the eyes to see this life of daily trust and daily bread as a joyous feast, as we are sustained by the bread of life, our Savior.

The Fallen Feasting of the First Adam

God’s first specific command is a command to fast and feast in a proper way. You can feast from all of this goodness, but not of one particular tree. Even in God’s good creation, a certain kind of fasting was called for, a fasting that recognized that God is God and we are not. Fasting helps us to understand our limits and God’s sovereignty. Fasting helps to properly “place” us within God’s world. But God’s good creation also had plenty of room for feasting. God tells Adam and Eve to enjoy the abundant goodness of all other trees in the garden. He had made these trees in part to provide the sustenance humans need to live and flourish in his world.

The intertwinement of fasting and feasting is important. If all they did was feast, there would be a strong likelihood that they would forget that the source of all this goodness is not the fruitful trees but God. So when God sets apart a tree that they may not eat from, it is a sign to them of their limits—they are the image of God, not God—and it is also a remembrance that the source of all good things is not something within creation but the Creator. So fasting from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil is not simply “fasting.” It is a recognition that we depend upon God, not food or anything else, for our life and abundance. This fasting inscribes them within an entire worldview and narrative. It is a fast that proclaims a vision of the entire world in which the man and woman find themselves, with God as good and gracious provider and humans as his dependent representatives in the world he has created.

But the man and the woman choose to feast. And just as fasting is never just fasting, so feasting is never just feasting. This feast was a declaration of independence and rejection. In this feast, the man and woman rejected the world as a gift of the good Creator and instead proclaimed that they would harvest the goods of the world and recognize no bounds on their consumption. This is a consuming feast, a feast that knows no boundaries and no limits. A consuming feast that will promote a vision of the world as a world existing to serve only my needs, my sinful wants, my sinful desires. Not only trees and fruits, but all good things given by the Creator will now be seen not as gifts, but as simply givens, there for my taking to do with what I will. This is a consuming feast that will, in the end, cave in on itself like a black hole, consuming the consumer and all else that comes within its orbit. Indeed, within a few short chapters of Genesis, we see that sin entails a de-creation, as God’s good world succumbs to the formlessness and void of the flood, with only Noah and his family escaping. Fallen feasting seems good at the time, but its end is death.

The Redemptive Fasting of the Second Adam (Matthew 4:1-4; Matthew 6:16-34)

The Second Adam is not feasting in a lush garden, but fasting in the desert of the real, the fallen world. When Jesus responds to the tempter, he is clear that it is not food but God who ultimately sustains us. Our practice of fasting helps us to remember that we depend for our existence and well-being ultimately on the Creator, not anything in creation, including food.

Jesus assumes that his disciples are going to fast. In Luke 5:35, Jesus says his followers will fast in the future, when he has ascended. But fasting is not done to impress others with how spiritual we are. In fact, Jesus says don’t let others know that you are doing this.

We should recognize that nothing shows a lack of dependence on God like the willingness to store up the world’s treasures for ourselves. Jesus says do not worry about your food or clothes; don’t worry about tomorrow. Now, this seems really hard. The problem is, we read these as Jesus telling us something impossible. He’s describing a radical kind of life that we can’t really do anyway. Maybe crazy monks or Shane Claiborne can just leave it all behind, but we can’t. If you’re going to be a pastor, youth minister, social worker, worship leader, educator, business person, or whatever, we have to plan for the future. But the rhetorical question Jesus poses, “what shall we eat?” comes from an Old Testament text about the Sabbath year: Leviticus 25.

In Leviticus 25, God commands Israel regarding the Sabbath year and year of Jubilee. For six years, the people were to harvest their fields and prune their vines. Every seven years, the land was to have a Sabbath rest. No harvesting, no pruning. On the one hand, this is a fast, a fast from working. Like Adam and Eve in the Garden, the people of Israel were called to recognize that what sustains them is not the fruit of the land, but God. This work stoppage, this fast from working, was a declaration of dependence on God.

But this was also a feast. God said that every sixth year he would provide more than enough to sustain the people through the Sabbath year and beyond. Deuteronomy 15 clarifies that this year also brings with it a proclamation of debt forgiveness. (All student loans will be forgiven!) Why? Deutueronomy 15:4 tells us so that “there will be no poor among you.” This was a year of feasting and partying. In that seventh year, there was food. Food was there, and the food of the land was for everyone: male and female, Jew and Gentile, slave and free. The Sabbath year is a year of leveling, a year in which all partake of God’s abundant provision, rejoice in the forgiveness of debts, and gather around the Lord’s table that he sets before his children.

So when Jesus echoes the question “What shall we eat?” and talks about pursuing the kingdom first, he is calling us to embrace the fasting and feasting of the Sabbath year. Jesus’ followers fast to inscribe into our very bodies the reality that we do not serve the god Mammon. Fasting gives us a new vision of the universe and all the good things the Father provides. We are called to write love not on our arms, but in our bellies. We therefore plow and harvest responsibly, but we do so not to hoard but so that there will be no needy among us, as Deut. 15:4 promises and Acts 4:34 fulfills. For the early church, the Sabbath year was not a once-every-seven-years proclamation, but a way of life. Indeed, we pray “give us this day our daily bread,” and “forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors.”

Jesus calls to renounce the consuming feast of the first Adam in order to embrace the self-giving fast of the Second Adam. In fasting, we are able to see the world as God sees it; we are able to pursue the kingdom first and trust that everything else will follow. Like the boy with five loaves and two fishes, we can let go of what we have and, when we do, we will miraculously find that the Lord of the feast provides all that we need and more. The Church, then, as the New Eve, ought to follow the lead of Christ her husband, resist temptation and remember that we do not live by bread alone but by God’s Word. The question is, in a world shaped by gluttony and greed, whether we have the eyes to see this life of daily trust and daily bread as a joyous feast, as we are sustained by the bread of life, our Savior.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed