Aristotle's thought gives Christians important tools to explain their objection to abortion in philosophical terms. Recent legislation by New York and Virginia has people focused on abortion again. The legal issues are certainly important, but beneath the legal questions, there lies a deeper philosophical question that divides those who support abortion and those who are against it: exactly what is the unborn baby and exactly what kind of change happens at birth?

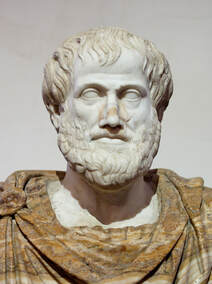

These questions—of something’s basic essence and of the nature of permanence and change—are as old as the pre-Socratic philosophers, all of whom grappled with how to understand reality and change. Dilemmas regarding permanence and change were addressed by Aristotle, whose philosophy is useful to pro-life Christians today who are trying to articulate how something stays the same (human person) through the process of change (birth). I want to briefly outline how Aristotelian philosophy equips Christians in philosophical discussions surrounding abortion.

In his Categories, Aristotle recognizes (in a less infamous fashion than President Bill Clinton) that the word “is” can be used in a variety of ways. In the summer, I might say “I am hot” or, when attending a crowded event, I might call out to my kids, “I’m over here!” Or I might say something like “That man is Aaron” or “Aaron is a man.” Aristotle recognized that the last two examples were getting at something permanent and enduring, which he called “essence” or “substance.” In contrast, the first two examples were true in the moment they were spoken—I really was quite warm, and I really was at that location at that time—but they were not enduring characteristics that describe the essence of who I am. For Aristotle, these unenduring characteristics were termed “accidents,” not because they happened when they weren’t supposed to (as in a “car accident”) but as a way to label things that could change but would not change the essence of what something is. Examples of these kinds of things are plentiful: my height, weight, age, geographical location, posture, temporary actions, and temporary states (like being hot or cold). These may change, but the kind of thing I am (a human being; what Aristotle calls “secondary substance”) and my being an individual (a particular human being; what Aristotle calls “primary substance”) do not change.

In the midst of all this philosophical jargon, I want to be clear that this distinction can be grasped by almost anyone. Even my kids get the basic Aristotelian distinction between substance and accidents, because a classic dad joke is premised on them. So when my daughter says, “Dad, I’m hungry,” and I respond, “Oh, hi Hungry! Nice to meet you!” I’m intentionally swapping out an accident for her primary substance (her name, which points to her individuality). She gets mildly annoyed with me, but she gets the joke, because even young children grasp this distinction that is so basic to language and ontology. This helps us see that Aristotle isn’t inventing these categories of substance and accidents; he’s merely observing and categorizing them.

Aristotle also distinguishes between two kinds of change, that which we call “life” and that which is not living. In his work De Anima (in the Latin, you can see the distinction we make between “animate” and “inanimate” objects), Aristotle outlines three kinds of life, nutritive (plants), perceptive (animals), and rational (humans). Inanimate objects change when acted on from outside, as when a rock is smoothed when water runs over it. Animate objects change because they have something internal that produces change, as when a tree grows because it is nourished by water and soil. For Aristotle, life entails a potential for growth and change that is driven internally, whereas non-living things have potential for change only insofar as something acts on them externally. Importantly, even though something living grows and changes, it does not change substantially only accidentally. By virtue of being a living thing, it is what it is through change and growth.

So how does this help us as we think about abortion and the status of unborn children? It gives us some basic philosophical tools to describe what many Christians hold implicitly about what kind of change birth is, and what kind of ontological status an unborn baby has. Most importantly, what happens at birth is not a substantial change. Birth is, in Aristotelian terms, an accidental change, a shift in location and type of dependency, but not a substantial change. It is certainly a change in location, from inside the womb to outside. And it is a change in relationship to the body of the mother, from being dependent in one form (especially nourishment through the umbilical cord) to being dependent in another form (breast milk and all kinds of daily necessities).

Sometimes proponents of abortion make too much of this dependency. It’s certainly true that a baby born prior to 24 weeks has little chance of surviving outside the womb (much later if there is not access to neonatal technology). But that doesn’t justify abortion. If it did, it would also justify the killing of most infants and toddlers, few if any of whom are able to survive independently outside the womb either. Furthermore, all life is dependent on what is outside itself to survive, so that objection—the baby is dependent on the mother—doesn’t sufficiently recognize the dependent nature of all life.

In contrast to birth, however, abortion is a substantial change, for both the actuality of the baby and its potentiality are fundamentally altered. The fact that an unborn baby has the potential to be a fully grown, mature human being underscores the fact that it already is a human being. Through intervention, however, he or she ceases to be alive. In Aristotelian terms, a synonym for “substantial change” for living beings is “death.”

So what is an unborn baby? A human being. And what kind of change happens at birth? A change that is accidental, not substantial. A change that does not alter the fundamental nature of the human being born. Aristotle thus provides useful tools to explain philosophically why, as rational and spiritual animals, it is immoral for us to take the life of unborn babies. Their difference from us is merely one of location, not of substance.

These questions—of something’s basic essence and of the nature of permanence and change—are as old as the pre-Socratic philosophers, all of whom grappled with how to understand reality and change. Dilemmas regarding permanence and change were addressed by Aristotle, whose philosophy is useful to pro-life Christians today who are trying to articulate how something stays the same (human person) through the process of change (birth). I want to briefly outline how Aristotelian philosophy equips Christians in philosophical discussions surrounding abortion.

In his Categories, Aristotle recognizes (in a less infamous fashion than President Bill Clinton) that the word “is” can be used in a variety of ways. In the summer, I might say “I am hot” or, when attending a crowded event, I might call out to my kids, “I’m over here!” Or I might say something like “That man is Aaron” or “Aaron is a man.” Aristotle recognized that the last two examples were getting at something permanent and enduring, which he called “essence” or “substance.” In contrast, the first two examples were true in the moment they were spoken—I really was quite warm, and I really was at that location at that time—but they were not enduring characteristics that describe the essence of who I am. For Aristotle, these unenduring characteristics were termed “accidents,” not because they happened when they weren’t supposed to (as in a “car accident”) but as a way to label things that could change but would not change the essence of what something is. Examples of these kinds of things are plentiful: my height, weight, age, geographical location, posture, temporary actions, and temporary states (like being hot or cold). These may change, but the kind of thing I am (a human being; what Aristotle calls “secondary substance”) and my being an individual (a particular human being; what Aristotle calls “primary substance”) do not change.

In the midst of all this philosophical jargon, I want to be clear that this distinction can be grasped by almost anyone. Even my kids get the basic Aristotelian distinction between substance and accidents, because a classic dad joke is premised on them. So when my daughter says, “Dad, I’m hungry,” and I respond, “Oh, hi Hungry! Nice to meet you!” I’m intentionally swapping out an accident for her primary substance (her name, which points to her individuality). She gets mildly annoyed with me, but she gets the joke, because even young children grasp this distinction that is so basic to language and ontology. This helps us see that Aristotle isn’t inventing these categories of substance and accidents; he’s merely observing and categorizing them.

Aristotle also distinguishes between two kinds of change, that which we call “life” and that which is not living. In his work De Anima (in the Latin, you can see the distinction we make between “animate” and “inanimate” objects), Aristotle outlines three kinds of life, nutritive (plants), perceptive (animals), and rational (humans). Inanimate objects change when acted on from outside, as when a rock is smoothed when water runs over it. Animate objects change because they have something internal that produces change, as when a tree grows because it is nourished by water and soil. For Aristotle, life entails a potential for growth and change that is driven internally, whereas non-living things have potential for change only insofar as something acts on them externally. Importantly, even though something living grows and changes, it does not change substantially only accidentally. By virtue of being a living thing, it is what it is through change and growth.

So how does this help us as we think about abortion and the status of unborn children? It gives us some basic philosophical tools to describe what many Christians hold implicitly about what kind of change birth is, and what kind of ontological status an unborn baby has. Most importantly, what happens at birth is not a substantial change. Birth is, in Aristotelian terms, an accidental change, a shift in location and type of dependency, but not a substantial change. It is certainly a change in location, from inside the womb to outside. And it is a change in relationship to the body of the mother, from being dependent in one form (especially nourishment through the umbilical cord) to being dependent in another form (breast milk and all kinds of daily necessities).

Sometimes proponents of abortion make too much of this dependency. It’s certainly true that a baby born prior to 24 weeks has little chance of surviving outside the womb (much later if there is not access to neonatal technology). But that doesn’t justify abortion. If it did, it would also justify the killing of most infants and toddlers, few if any of whom are able to survive independently outside the womb either. Furthermore, all life is dependent on what is outside itself to survive, so that objection—the baby is dependent on the mother—doesn’t sufficiently recognize the dependent nature of all life.

In contrast to birth, however, abortion is a substantial change, for both the actuality of the baby and its potentiality are fundamentally altered. The fact that an unborn baby has the potential to be a fully grown, mature human being underscores the fact that it already is a human being. Through intervention, however, he or she ceases to be alive. In Aristotelian terms, a synonym for “substantial change” for living beings is “death.”

So what is an unborn baby? A human being. And what kind of change happens at birth? A change that is accidental, not substantial. A change that does not alter the fundamental nature of the human being born. Aristotle thus provides useful tools to explain philosophically why, as rational and spiritual animals, it is immoral for us to take the life of unborn babies. Their difference from us is merely one of location, not of substance.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed