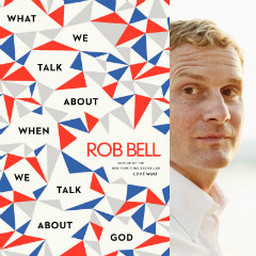

Even though he's departed Grand Rapids and traded provoking angry tweets for surfing, I try to keep up with what Rob Bell's doing. As I've said before, I'm not a "farewell, Rob Bell" person. I appreciate much of what he's done and written, while also scratching my head about other things. This past week I read through his latest book, What We Talk About When We Talk About God. It's been a few months since it released to much less hubbub than Love Wins. Let me first summarize the book's chapters (each titled with a single word) in a sentence or two.

Summary

Hum: We all have glimpses or moments where we get a sense of something more, something that transcends "ordinary" existence but is not other than ordinary existence--it's the perception that the ordinary is itself quite extraordinary. But sometimes we don't perceive this as God because some people think about God like Rob's old Oldsmobile: old, dusty, left behind, outdated.

Open: Contemporary science is stranger than science fiction. If you can be open to quantum physics, you should be open to God. It's not those who believe in God who are "close-minded," but those who refuse to do so (take that Richard Dawkins!).

Both: We use words to talk about God but we must recognize that our words ultimately fall short of the reality of God. But we shouldn't stop talking about God, but recognize this fact about our language for God.

With: God isn't a deistic god who pops in from time to time, God is always with us.

For: God isn't an angry god who wants to smite you, God is fundamentally for us.

Ahead: God isn't behind us (even if those fundamentalist Christians are), God is ahead of us, calling us further into what God's doing.

So: There's not a spiritual/secular dualism. All spaces are sacred. God is ever-present with us and in us. Open your eyes and see.

Open: Contemporary science is stranger than science fiction. If you can be open to quantum physics, you should be open to God. It's not those who believe in God who are "close-minded," but those who refuse to do so (take that Richard Dawkins!).

Both: We use words to talk about God but we must recognize that our words ultimately fall short of the reality of God. But we shouldn't stop talking about God, but recognize this fact about our language for God.

With: God isn't a deistic god who pops in from time to time, God is always with us.

For: God isn't an angry god who wants to smite you, God is fundamentally for us.

Ahead: God isn't behind us (even if those fundamentalist Christians are), God is ahead of us, calling us further into what God's doing.

So: There's not a spiritual/secular dualism. All spaces are sacred. God is ever-present with us and in us. Open your eyes and see.

Critique

There are some worthwhile elements in the book. Bell's translation of some aspects of contemporary science is entertaining, as he takes you on the mind-blowing journey with him. His chapter on language seems basic, in that it seems to suggest an analogical view of language for God, but also potentially problematic, in that it seems to make more of God's being "beyond words" than that God has revealed himself in words of Scripture and supremely in the Word, Jesus Christ. I get a bit worried here because often when people begin to speak of God being "beyond words," it's not long before they start to doubt that God reveals himself in any specific way, much less the very particular Jesus of Nazareth. The chapters on a God who is with and for seem like no-brainers to some extent, but the fact that he needs to write these is a sign that Christians often don't convey these basic truths very well. The chapter on God being "ahead" of us points out a key observation of biblical interpretation courses everywhere: you have to read the Bible in its original context (not ours) and understand that it's a story that's going somewhere. Once you do this, you can start to grasp how revolutionary it is and recognize the call to continue living out that story today. John Howard Yoder talks about this as the "directional movement" of Scripture (search "directional" on the Yoder Index for references). Baptist scholar William Webb outlines this way of reading in his book Slaves, Women, and Homosexuals, Sarah Rudin highlights it in Paul Among the People, and Mark Strauss calls this way of reading a "heart of God" hermeneutic in his book How to Read the Bible in Changing Times. Throughout the book, my perception is that Bell is at his strongest as a communicator and interpreter of the good books he's read. And as with his other books, no one will mistake Bell for a systematic theologian who prioritizes precision and coherence. Rather, he paints with impressionistic flair, passionate for readers to catch a glimpse of what he's seen. I try to appreciate that for what it is, even though the systematic theologian side of me sometimes wants to scream, "But what does that actually mean?"

As I read the book, two words kept coming to mind: Friedrich Schleiermacher (the title of this post is a play on his book On Religion: Speeches to Its Cultured Despisers). As the saying goes, those who don't know the past are doomed to repeat it. Now, I'm not comparing Bell to the philosophical and theological genius of Schleiermacher. But if you don't know who Schleiermacher is, here's a little history lesson, courtesy of John Nugent, who gives a clear and concise summary of the Schleiermacher (aka the father of modern theology):

"In the early 19th century, Friedrich Schleiermacher (you can call him Fred if that helps) sought to make Christianity acceptable to the religious despisers of his day. The Romanticism of that time was known for its rejection of institutional religion. Such religion was perceived to be steeped in religiosity and unnecessarily encumbered with specific traditions and doctrines. They were especially critical of intellectual and ethical approaches to religion.

Sound familiar?

Sharing those sensibilities, yet not wishing to drain the baby out with the bathwater, Fred redefined Christianity along lines that were acceptable to himself and his peers. His most decisive move was to identify the core of religion with the individual’s feeling of complete dependence on the divine, the infinite, or the absolute. This immediate personal experience, which cannot be received from others, stands at the core of one’s faith. This “feeling” became the throne before which all other practices and institutions must bow."

To me, this book reads like Bell's attempt to make God palatable to those for whom God is not really a workable concept. I get that, and I'm sympathetic. What's interesting is that throughout the book, Bell's move seems to parallel Schleiermacher's: focus on religion as the individual's feeling of dependence and recognition that one is part of something much bigger and much more amazing that one could think. That's not a bad thought, nor untrue. But neither is it specifically Christian. As I was re-reading the entry on Schleiermacher on the Stanford Philosophy site, several other quotes were striking, in that these could just as easily have been descriptions of Bell's thought:

Characterizing Bell's approach in this book as "based on intuition or feeling" as opposed to thinking or acting seems exactly right to me. My worry--which might be completely unfounded, by the way--is that Bell seems to moving further and further away from the specificity of the Christian narrative, with a robust emphasis on Israel, Jesus, and the church toward a vague, generalized God. I've always appreciated the way that Mars Hill Bible Church, at least in part under Bell's leadership, embraced (and continues to embrace) narrative theology. But this is where Paul's speech at Mars Hill in Acts 17 can be instructive. Paul begins with a vague, generalized, unknown God, but doesn't stay there; in fact, he gets very specific. God is done overlooking ignorance; he's appointed a day of judgment; the Judge is Jesus because it is Jesus who has been raised from the dead (Acts 17:30-31). It's hard to get more specific than that. And that message didn't sit well with many at Athens. By contrast, Bell concludes his book by highlighting yoga, yawning when someone else yawns, neuroplasticity, feng shui, architecture, and a surfer who sees God everywhere. Hear me clearly: I'm not saying that Bell has turned his back on Jesus. But his rhetorical strategy is clearly to focus on something other than the specificity of Jesus in order to explain "what we talk about when we talk about God." In other words, he seems to have left Mars Hill behind in more ways than one.

Related post: "What We Talk About When We Say 'You Can't Put God in a Box'"

As I read the book, two words kept coming to mind: Friedrich Schleiermacher (the title of this post is a play on his book On Religion: Speeches to Its Cultured Despisers). As the saying goes, those who don't know the past are doomed to repeat it. Now, I'm not comparing Bell to the philosophical and theological genius of Schleiermacher. But if you don't know who Schleiermacher is, here's a little history lesson, courtesy of John Nugent, who gives a clear and concise summary of the Schleiermacher (aka the father of modern theology):

"In the early 19th century, Friedrich Schleiermacher (you can call him Fred if that helps) sought to make Christianity acceptable to the religious despisers of his day. The Romanticism of that time was known for its rejection of institutional religion. Such religion was perceived to be steeped in religiosity and unnecessarily encumbered with specific traditions and doctrines. They were especially critical of intellectual and ethical approaches to religion.

Sound familiar?

Sharing those sensibilities, yet not wishing to drain the baby out with the bathwater, Fred redefined Christianity along lines that were acceptable to himself and his peers. His most decisive move was to identify the core of religion with the individual’s feeling of complete dependence on the divine, the infinite, or the absolute. This immediate personal experience, which cannot be received from others, stands at the core of one’s faith. This “feeling” became the throne before which all other practices and institutions must bow."

To me, this book reads like Bell's attempt to make God palatable to those for whom God is not really a workable concept. I get that, and I'm sympathetic. What's interesting is that throughout the book, Bell's move seems to parallel Schleiermacher's: focus on religion as the individual's feeling of dependence and recognition that one is part of something much bigger and much more amazing that one could think. That's not a bad thought, nor untrue. But neither is it specifically Christian. As I was re-reading the entry on Schleiermacher on the Stanford Philosophy site, several other quotes were striking, in that these could just as easily have been descriptions of Bell's thought:

- Schleiermacher conceives of a basic monistic principle as "an original force and the unifying source of a multiplicity of more mundane forces."

- "For Schleiermacher religion is based neither on theoretical knowledge nor on morality. According to On Religion, it is instead based on an intuition or feeling of the universe: 'Religion's essence is neither thinking nor acting, but intuition and feeling. It wishes to intuit the universe.'"

- Religion is a "feeling of absolute dependence."

- "He works to salvage the Christian doctrine of miracles in the modified form of a doctrine which includes all events as miracles."

Characterizing Bell's approach in this book as "based on intuition or feeling" as opposed to thinking or acting seems exactly right to me. My worry--which might be completely unfounded, by the way--is that Bell seems to moving further and further away from the specificity of the Christian narrative, with a robust emphasis on Israel, Jesus, and the church toward a vague, generalized God. I've always appreciated the way that Mars Hill Bible Church, at least in part under Bell's leadership, embraced (and continues to embrace) narrative theology. But this is where Paul's speech at Mars Hill in Acts 17 can be instructive. Paul begins with a vague, generalized, unknown God, but doesn't stay there; in fact, he gets very specific. God is done overlooking ignorance; he's appointed a day of judgment; the Judge is Jesus because it is Jesus who has been raised from the dead (Acts 17:30-31). It's hard to get more specific than that. And that message didn't sit well with many at Athens. By contrast, Bell concludes his book by highlighting yoga, yawning when someone else yawns, neuroplasticity, feng shui, architecture, and a surfer who sees God everywhere. Hear me clearly: I'm not saying that Bell has turned his back on Jesus. But his rhetorical strategy is clearly to focus on something other than the specificity of Jesus in order to explain "what we talk about when we talk about God." In other words, he seems to have left Mars Hill behind in more ways than one.

Related post: "What We Talk About When We Say 'You Can't Put God in a Box'"

RSS Feed

RSS Feed