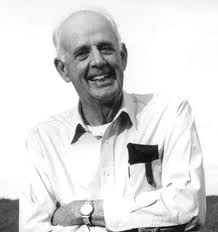

Wendell Berry is far and away one of my favorite writers. I'm currently reading his new collection of short stories, A Place in Time. While flipping through one of his books of essys the other day, I came across this discussion of pluralism. I could give commentary on what he says, but I'll just let the text stand as it is. It's hard to improve on Berry.

"There is, in fact, a good deal of talk about pluralism these days, but most of it that I have seen is fashionable, superficial, and virtually worthless. It does not foresee or advocate a plurality of settled communities but is only a sort of indifferent charity toward a plurality of aggrieved groups and individuals. It attempts to deal liberally--that is, by the superficial courtesies of tolerance and egalitarianism--with a confusion of claims.

The social and cultural pluralism that some now see as a goal is a public of destroyed communities. Wherever it exists, it is the result of centuries of imperialism. The modern industrial urban centers are 'pluralistic' because they are full of refugees from destroyed communities, destroyed community economies, disintegrated local cultures, and ruined local ecosystems. The pluralists who see this state of affairs as some sort of improvement or as the beginning of 'global culture' are bein historically perverse, as well as politically naive. They wish to regard liberally and tolerantly the diverse, sometimes competing claims and complaints of a rootless society, and yet the continue to tolerate also the ideals and goals of the industrialism that caused the uprooting. They affirm the pluralism of a society formed by the uprooting of cultures at the same time that they regard the fierce self-defense of still-rooted cultures as 'fundamentalism,' for which they have no tolerance at all. They look with wistful indulgence and envy at the ruined or damaged American Indian cultures so long as those cultures remain passively a part of our plurality, forgetting that these cultures, too, were once 'fundamentalist' in their self-defense. And when these cultures again attempt self-defense--when they again assert the inseparability of culture and place--they are opposed by this pluralistic society as self-righteously as ever. The tolerance of this sort of pluralism extends always to the uprooted and passive, never to the rooted and active...

Any group that takes itself, its culture, and its values seriously enough to try to separate, or to remain separate, from the industrial line of march will be, to say the least, unwelcome in the plurality. The tolerance of these doctrinaire pluralists always runs aground on religion. You may be fascinated by religion, you may study it, anthropologize and psychoanalyze about it, collect and catalogue its artifacts, but you had better not believe it. You may put into 'the canon' the holy books of any group, but you had better not think them holy. The shallowness and hypocrisy of this tolerance is exposed by its utter failure to extend itself to the suffering people in Iraq [this piece was written in 1992], who are, by the standards of this tolerance, fundamentalist, backward, unprogressive, and in general not like 'us.'...

That there should be peace, commerce, and biological and cultural outcrosses among local culture is obviously desirable and probably necessary as well. But such a state of things would be radically unlike what is now called pluralism. To start with, a plurality of settled communities could not be preserved by the present-day pluralists' easy assumption that all cultures are equal or of equal value and capable of surviving together by tolerance. The idea of equality is a good one, so long as it means 'equality before the law.' Beyond that, the idea becomes squishy and sentimental because of the manifest inequalities of all kinds...If we have equality and nothing else--no compassion, no magnanimity, no courtesy, no sense of mutual obligation and dependence, no imagination--then power and wealth will have their way; brutality will rule. A general and indiscriminate egalitarianism is a free-market culture, wihch, like free-market economics, tends toward a general and destructive uniformity. And tolerance, in association with such egalitarianism, is a way of ignoring the reality of significant differences. If I merely tolerate my neighbors on the assumption that all of us are equal, that means I can take no interest in the question of which ones of us are right and which ones are wrong; it means that I am denying the community the use of my intelligence and judgment; it means that I am not prepared to defer to those whose abilities are superior to mine, or to help those whose condition is worse; it means that I can be as self-centered as I please."

- from "Sex, Economy, Freedom, and Community," in The Art of the Commonplace, pp. 178-181

"There is, in fact, a good deal of talk about pluralism these days, but most of it that I have seen is fashionable, superficial, and virtually worthless. It does not foresee or advocate a plurality of settled communities but is only a sort of indifferent charity toward a plurality of aggrieved groups and individuals. It attempts to deal liberally--that is, by the superficial courtesies of tolerance and egalitarianism--with a confusion of claims.

The social and cultural pluralism that some now see as a goal is a public of destroyed communities. Wherever it exists, it is the result of centuries of imperialism. The modern industrial urban centers are 'pluralistic' because they are full of refugees from destroyed communities, destroyed community economies, disintegrated local cultures, and ruined local ecosystems. The pluralists who see this state of affairs as some sort of improvement or as the beginning of 'global culture' are bein historically perverse, as well as politically naive. They wish to regard liberally and tolerantly the diverse, sometimes competing claims and complaints of a rootless society, and yet the continue to tolerate also the ideals and goals of the industrialism that caused the uprooting. They affirm the pluralism of a society formed by the uprooting of cultures at the same time that they regard the fierce self-defense of still-rooted cultures as 'fundamentalism,' for which they have no tolerance at all. They look with wistful indulgence and envy at the ruined or damaged American Indian cultures so long as those cultures remain passively a part of our plurality, forgetting that these cultures, too, were once 'fundamentalist' in their self-defense. And when these cultures again attempt self-defense--when they again assert the inseparability of culture and place--they are opposed by this pluralistic society as self-righteously as ever. The tolerance of this sort of pluralism extends always to the uprooted and passive, never to the rooted and active...

Any group that takes itself, its culture, and its values seriously enough to try to separate, or to remain separate, from the industrial line of march will be, to say the least, unwelcome in the plurality. The tolerance of these doctrinaire pluralists always runs aground on religion. You may be fascinated by religion, you may study it, anthropologize and psychoanalyze about it, collect and catalogue its artifacts, but you had better not believe it. You may put into 'the canon' the holy books of any group, but you had better not think them holy. The shallowness and hypocrisy of this tolerance is exposed by its utter failure to extend itself to the suffering people in Iraq [this piece was written in 1992], who are, by the standards of this tolerance, fundamentalist, backward, unprogressive, and in general not like 'us.'...

That there should be peace, commerce, and biological and cultural outcrosses among local culture is obviously desirable and probably necessary as well. But such a state of things would be radically unlike what is now called pluralism. To start with, a plurality of settled communities could not be preserved by the present-day pluralists' easy assumption that all cultures are equal or of equal value and capable of surviving together by tolerance. The idea of equality is a good one, so long as it means 'equality before the law.' Beyond that, the idea becomes squishy and sentimental because of the manifest inequalities of all kinds...If we have equality and nothing else--no compassion, no magnanimity, no courtesy, no sense of mutual obligation and dependence, no imagination--then power and wealth will have their way; brutality will rule. A general and indiscriminate egalitarianism is a free-market culture, wihch, like free-market economics, tends toward a general and destructive uniformity. And tolerance, in association with such egalitarianism, is a way of ignoring the reality of significant differences. If I merely tolerate my neighbors on the assumption that all of us are equal, that means I can take no interest in the question of which ones of us are right and which ones are wrong; it means that I am denying the community the use of my intelligence and judgment; it means that I am not prepared to defer to those whose abilities are superior to mine, or to help those whose condition is worse; it means that I can be as self-centered as I please."

- from "Sex, Economy, Freedom, and Community," in The Art of the Commonplace, pp. 178-181

RSS Feed

RSS Feed